Written by George Perry, June 2021

For 1000s of years, western philosophy has taught us about the ‘art’ of public speaking. Going back to the ancient Greeks, Aristotle and his protégé Plato (and also Socrates that came before him – and many others) were determined to tell us that Logos, Pathos, and Ethos were what we needed to communicate with conviction.

For 1000s of years, western philosophy has taught us about the ‘art’ of public speaking. Going back to the ancient Greeks, Aristotle and his protégé Plato (and also Socrates that came before him – and many others) were determined to tell us that Logos, Pathos, and Ethos were what we needed to communicate with conviction.

Starting from the 5th century until around 300 BC – so we are talking nearly 2.5 millennia ago – philosophy had a different meaning (or rather a different connotation) to what we now understand it to be.

The Ancients

Usually when people think of philosophy in this day and age, we imagine self-proclaimed intellectual types sitting around debating things of an abstract nature that don’t have a particular influence on our everyday lives. Those philosophers would say it does, but most other people would beg to differ.

Back in the time of the ancients, philosophy was more focused on something much more tangible – making sense of the world around them. Philosophy was used in very real-world scenarios as a tool to help understand the real world, at a time that allegedly led to civilisation.

So, with this in context, perhaps it is understandable why those early philosophical teachings have had such an enduring effect on the world today. We could, in fact, debate all day long whether it was actually philosophy or not that Greeks were philosophizing about; and, in fact, this ties in with the very nature of the beast, as they championed debate.

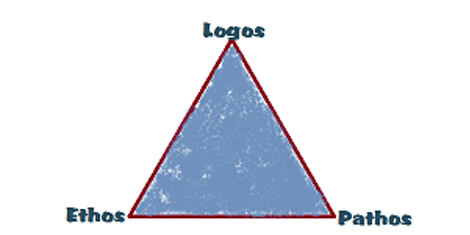

Logos, Pathos, Ethos

In no particular order, their first offering was Logos, meaning argumentation based on reasoning and facts. For Logos, the focus is placed on who is ‘right’ or ‘wrong’ in a debate, albeit this not needing to be based on the facts, but on who can present the facts in the most convincing way so as to ‘win’ the argument.

In essence, they viewed argumentation as being more of a sport, with sparring partners, a competition, and winners or losers. Another way of looking at it, as I mentioned above, is that they treated more like an art form.

As you might imagine, not actually having to be right or wrong per se (which we could debate, or philosophize, on the true meaning of right vs. wrong in itself for time eternal), but only needing to win the argument based on the way you present the facts, must be music to any politicians’ ears.

Forgive me if that sounds cynical, but the modern political system is very much based on this very idea at its core – the UK parliament, a debating chamber, being the very exemplar of what Aristotle would enjoy as a decent argument.

The Art of Persuasion

Pathos delves into different territory, as while Logos is concerned with making your words make sense, Pathos is focused on how you present those words. It is something much more psychological, and some would argue* (*disclaimer: they would argue in an entirely orderly and logical way!) that Pathos is more of an important element in the art of persuasion than is Logos.

Pathos delves into different territory, as while Logos is concerned with making your words make sense, Pathos is focused on how you present those words. It is something much more psychological, and some would argue* (*disclaimer: they would argue in an entirely orderly and logical way!) that Pathos is more of an important element in the art of persuasion than is Logos.

To synthesise, Logos is about getting your audience to think, while Pathos is all about getting your audience to feel. If they don’t feel emotion, you don’t tug on their heartstrings in some way, then you have zero chance of winning any debate, or so they say.

In many ways, this does make perfect sense as humans are emotional, sensing beings. Due to this outstanding factor, whether right or wrong, you may even be able to win an argument based on Pathos alone. But this would only be in certain situations, and isn’t very likely.

Logos assumes that humans are robotic, logical beings that process thoughts based on pure facts (or rather, the way in which they’re presented); whereas Pathos assumes that arguments can be won by appealing to only the fragility of humans that makes them act irrationally – their emotions.

Combing Forces

The reality is that when it comes to persuading people around to our way of thinking, we need both Logos and Pathos in equal measures. To be able to truly win an argument, you need that healthy mixture of persuading peoples’ rational and irrational sides.

Recognizing this is something that the Greeks did well, and then used to their advantage. They could see that that humans are imperfect, and rather than try to stamp this out and assume that people ought to act more robotically, they realised that it is best to accept human beings, for all their flaws, and take the benefit from that when it comes to winning a debate.

The final piece of the puzzle that they offered when it came to power of persuasion is Ethos. As you might imagine, this is where we get the word ‘ethics’ from, which in its purest form essentially means getting people to trust you because you have a humane morality that appeals to them. Achieving this could be done by establishing your credentials with your audience.

Just as with Logos and Pathos, Ethos should be applied in equal measure, and it is thought that the true way to get people to respect you is through a balanced distribution of Logos, Pathos, and Ethos when presenting a narrative.

Enduring through the Ages

So, to summarise, we can say that Logos is about how you structure your speech (apply logic); Pathos is about how we can add emotional value to our oration (essentially, our story-telling technique); and Ethos is about gaining that necessary trust through credibility (how confident people can feel to believe what you say).

Aside from my tongue-in-cheek interpretation of politicians essentially applying some ancient philosophical techniques to persuade people, I’m sure that any trained barrister would also tell you of the value of applying all three, with ample amount of Ethos being necessary in the profession alongside Pathos and Logos.

Aside from my tongue-in-cheek interpretation of politicians essentially applying some ancient philosophical techniques to persuade people, I’m sure that any trained barrister would also tell you of the value of applying all three, with ample amount of Ethos being necessary in the profession alongside Pathos and Logos.

As I mentioned above, what was lain out before us over 2,000 years ago by the ancient Greeks has endured to the present day because those early forerunners were very right in many ways about the way we structure society, and how humans interact with each other.

Applying the Techniques

In our latest podcasts, we interviewed Karen Dean about The Art of Storytelling, which as you’ll see from my descriptions above relates to the second offering from the Greek Philosophers – Pathos. Karen believes that providing a narrative can create the conditions for a leader to enable their organisations to be healthy, happy, successful, inclusive, agile, and sustainable.

In short, this is a skill that any leader can develop to inspire those around them and to model leading beyond their ego.

Karen says that a leader is there to lead people, and to be there for people; and so, connection is absolutely vital. She feels that the key to all this is being a charismatic story teller that makes others believe in them, and also want to follow them (hence, being a leader). Furthermore, an inspiring story teller enables an individual to believe in themselves.

In other words, Karen is not only alluding to the need for Pathos, but also you can see here the appeal to Ethos.

Metaphorically Speaking

Karen goes onto say that storytelling is important because it creates the conditions for people to feel part of something they can recognise, and also share their own experiences. If the behaviours that the leader is offering matches the story they’re telling, then this has the potential to inspire others around them.

Storytelling can be used to create the conditions for change. Karen tells us that using metaphors is a crucial factor in this, as people need the references to be able to acknowledge their experiences. The word ‘metaphor’, as you may know already, is a Greek one; and so there we have it, some Logos folding into the mix, as using metaphors in our speech is considered part of this.

We have now used all elements of Logos, Pathos, and Ethos as part of our storytelling, so this seems to suggest that any compelling narrative needs a healthy balance of all three of these elements – the Greeks had it right.

The Power of Engagement

Using stories as a tool is clever, as they entice engagement. Any engaged listener is more likely to take on board what you’re trying to put across to them. Storytelling enhances engagement because it changes the way we perceive information.

Using stories as a tool is clever, as they entice engagement. Any engaged listener is more likely to take on board what you’re trying to put across to them. Storytelling enhances engagement because it changes the way we perceive information.

All experiences of people are perceived through the five senses – what they see, hear, smell, taste, and touch. From this, people create an internal representation in their minds, which acts like a kind of signature; and this means that, any one of those senses alerted in the same way will remind us of the experience.

By listening to a story, and therefore listening to the way things are described in lieu of the actual senses being invoked, this has more ability to allow us to connect with the information, understand it, and remember it. A story can provide that internal feeling, taste, smell, or visualisation. This engages a part of the brain that is future-orientated, can release oxytocin, and brings the bond of connecting with others.

A good narrative ought to be sensory, and leaders can apply this to their storytelling. If a leader can produce a story that creates the flow of oxytocin which bonds their listeners to the narrative, this provides for an incredibly powerful engagement tool.

Authors are known to use all emotive language that pulls readers into their fiction, and leaders can do the same when it comes to telling real-life stories.

Top Tips for Storytelling

Karen’s top tips for leaders to feel confident when using stories to move their organisations are:

- Simplicity – stories need to be simple to be effective

- Detail – make your story full of vivid sensory detail

- Reality – stories ought to be real and relatable

- Authenticity – storytelling that flows through the leader

In addition, consider how real feelings can provide meaning for those listening to the story so as to generate curiosity, create a buzz, and get people sharing ideas.

The ideal story ought to acknowledge the past, help people make sense of the present, and excite them about the future. In this way, leaders inspire, and this inspiration can be, in turn, passed down to your client base.

Both parts of Karen Dean’s podcasts on “The Art of Narrative Storytelling” can be accessed here.